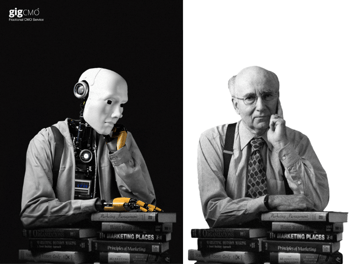

Digital transformation, marketing automation, multichannel distribution, SEO, PPC, CTR and an evolved view on artificial intelligence. They’re all part of the expected lexicon of today’s marketing leader. However, for all the technology and analysis in the world, it’s no good without understanding human behaviour. The result is that for those investing in lots of exciting technology, without really knowing why, it can feel like a scene from Raiders of The Lost Ark; we’re searching for treasure, but we’re digging in the wrong place.

Pots of cash

Human behaviour is not something an algorithm can necessarily predict. It’s more nuanced than that and it’s not always obviously rational. The biggest drivers in human behaviour are often emotion and habit.

Let’s take finance as the working example of marketing and human behaviour. Beyond the typical demographic targeting descriptors of age, income, sex, wealth and media consumption. How do people actually think, feel and behave when it comes to money?

Back when cash was king, the idea of “pots” in terms of people’s relationship with money was easy to understand and visualise. Imagine the mantelpiece with a jam jar allocated to rent. Another for household bills and another for holidays. This is still a pretty relevant idea. The 2017 Nobel Prize winner for Economics, Richard Thaler called it “mental accounting”.

He meant that the source and use of money impacts behaviour beyond a purely rational cost/benefit analysis. Thaler is probably the most prominent thinker in this space. But increasingly the discipline of behavioural science is making itself heard in terms of how psychology and economics align.

Conflicted thinking

An example in personal finance would be the person who is saving for a specific purpose such as a holiday or a wedding. They save through a bank deposit account paying less than 2% interest whilst at the same time having a credit card debt charging 25-30%. The financially rational thing to do would be to use the holiday/wedding fund to pay off the credit card. However, the human emotional attitude to the two distinctive pots prevents this.

Equally, when it comes to saving and investing, understanding how people inherently feel about short-term and long-term trade offs helps providers develop and present the right offer. As humans, we feel short-term losses more strongly than the prospect of future gains. This can be seen acutely in the UK pension industry today. Auto-enrolment introduced in 2012 has been a huge success, with 10 million people signed up. However, contribution levels bump along at low levels leaving potentially millions of people with inadequate retirement funding. Meanwhile, the industry and government have the pressing challenge of how to persuade or compel people to act in their own financial self-interest.

Generally, we seem to be losing the saving habit. Currently we save only 4% of disposable income vs 15% in the 1990’s according to the UK’s Office of National Statistics. This could be rationalised as low interest rates representing a disincentive and people paying down debt. However, record levels of household debt seems to negate that. More likely, advances in technology have helped reduce barriers to spending. For example, 78% of US millennials report having made “split second” buying decisions whilst shopping online (ING 2018).

It’s easier than ever to create good and bad habits

Much of purchase behaviour, including how we manage our finances, is habitual. As technology allows us to cement or amend those habits there are opportunities and obligations for marketers.

Mega trends such as living longer, greater retirement aspirations and more flexible working patterns, including non economically active periods. These lend themselves to the greater need for people to acquire greater financial freedom through acquiring greater financial resource.

For example, to date the financial services industry and FinTech entrants have, on the face of it, been more successful deploying tech and new media in the borrowing and spending arena rather than savings and investment. The results are counter intuitive. We should be trying to save more than ever, but it’s easier to see the impact of spending now than saving for later. So insight into how people think, feel and behave is essential to unlocking the other side of the equation.

In short, for marketers, technological progression and understanding human behaviour go hand in hand. One will not maximise its success without the other. It’s about having genuine customer focus, which is what the gigCMO team’s experience offers across the spectrum.